The Ozempic Economy: Beauty Standards, Black Markets, and the Price of Perfection

So what happens when a drug becomes wildly desirable but prohibitively expensive? An underground black market? Another beauty trend? Let's unpack everything...

What happens when a diabetes medication becomes the fastest beauty trend of the decade?

Well, what began as a Type 2 diabetes treatment has evolved into a $491 million marketing phenomenon, influencing industries from fashion, where recent runways featured just 0.8% plus-size models, to food, with brands launching products labeled “GLP-1 friendly.”

I recently published a LinkedIn post exploring how Ozempic has quietly become one of the most disruptive forces in consumer culture and it started a much-needed conversation about the growing divide not just in access, but health narratives, black-market trade networks, body image to retail strategy and public policy.

In other words, we’re in the Ozempic era.

And while a lot of marketers are scrambling to keep up with this shift…the real question isn't whether this trend will continue, it's whether we'll handle it responsibly.

Here’s a preview of what’s being covered in this series:

The history of body trends: How we got to the Ozempic era

The $491 million marketing budget: How pharma marketing shaped the trend

The access divide: Who gets these drugs and who gets left behind

Industry implications: What GLP‑1s mean for beauty, fashion, fitness, and food

The ethical reckoning: What role marketers play in shaping body ideals

Strategic steps: How to stay relevant without selling out

This piece does not aim to pass judgment on anyones choices regarding their body image or medical treatment. Instead, the point is to examine the broader marketing, societal, and ethical implications of an evolving trend. This is part 1.

The history of body trends:

To really understand the era we’re in, we need to zoom out because this isn’t the first time body trends have dictated culture, consumer behaviour and even healthcare access.

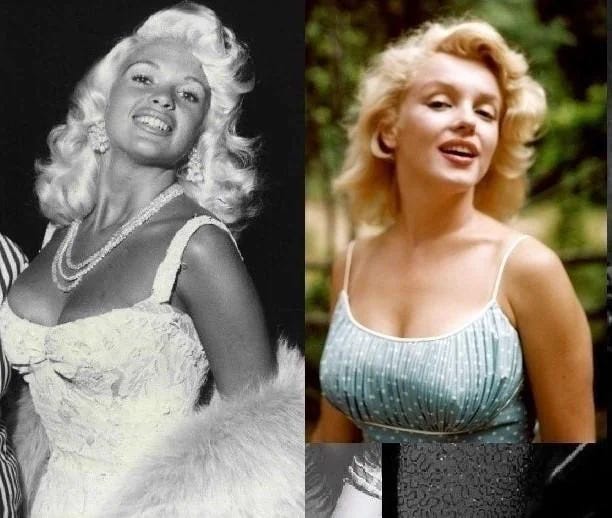

1950s: Marilyn Monroe, Jayne Mansfield and Betty Page were considered the sex symbols. They had long legs and busty hourglass figures. Ads of the era even advised "skinny" women to take weight-gain supplements to fill out their curves.

The Heroin Chic Era (1990s): Pale skin, dark under-eye circles, and extreme thinness dominated fashion. Models suffered from anorexia and heroin abuse to achieve this look.

The Video Vixen Era (Late 1990s-2000s): Video vixens like Melyssa Ford, Karrine Steffans, and Buffie "The Body" Carruth became the new beauty icons, setting standards with their "bodacious bodies". It was all about big boobs, flat stomach, big butt (pre-BBL), glossy lips, belly rings, and low-rise jeans.

The BBL and Filler Era (2010s): Kim Kardashian, Nicki Minaj and the Instagram generation brought us curves again via cosmetic procedures. The Brazilian butt lift became the surgery du jour.

2020s: Return of the Thin? / “Soft Curves” / Ozempic Era: The 2020s have seen quite a lot of beauty trends. At the start of the decade, the “slim thick” body was still aspirational, BBLs, snatched waists, and exaggerated curves were everywhere.

But something started to shift, slowly and then all at once.

Celebrities long associated with curvier figures started appearing noticeably slimmer, prompting public speculation about everything from reversed surgeries to new wellness routines.

It didn’t take long before major outlets like The Wall Street Journal and The New York Times began reporting on a common thread behind the transformation, Ozempic.

What started as a legitimate treatment for Type 2 diabetes has since expanded well beyond its original medical purpose.

The Numbers Behind the Trend

Between 2018 and 2022, prescriptions for semaglutide drugs (Ozempic, Wegovy, Rybelsus) grew from around 445,000 to 13.5 million in the US, covering roughly 3.3 million patients.

Initially, most of these prescriptions were for Type 2 diabetes, primarily among older adults with chronic conditions. But that changed pretty quickly as the public got hold of the fact that the drug was good for weight loss (among other things)

It went from doctors rooms to word of mouth to full blown marketing campaigns.

Pharmaceutical companies began expanding how they positioned semaglutides, framing them not only as diabetes treatments but also as tools for broader chronic weight management.

After launching Ozempic in 2018, Novo Nordisk heavily invested in both healthcare provider and direct-to-consumer marketing.

And that’s probably when more and more people started to take notice.

Over a ten-year period, the company spent at least $25.8 million in payments to leading obesity specialists, covering consulting fees, speaking engagements, and sponsored events, to help position these medications as part of the solution to the “obesity crisis.”

By mid-2022, Novo Nordisk had increased its advertising spend on Ozempic, Wegovy, and Rybelsus to nearly $491 million, a 21% year-over-year increase. Ozempic and Rybelsus accounted for $245 million of that total, while Wegovy’s marketing budget grew more than 1,000% as the drug gained traction as an official weight-loss aid.

Even before Wegovy received FDA approval for weight management in 2021, some doctors were already prescribing Ozempic off-label for patients looking to lose weight.

As more people saw visible results, word-of-mouth fueled awareness, well before formal ad campaigns gained the momentum they have now.

A 2025 study found that the share of new Ozempic users without a diabetes diagnosis rose from 9% in 2019 to 37% in 2022 meaning over a third were taking it for reasons other than blood sugar control .

So by the time celebrities began appearing noticeably slimmer and TikTok speculation took hold, the infrastructure of demand was already built. The cultural moment simply caught up to what had been building quietly through prescriptions, peer influence, and evolving narratives around body image and biology.

Importantly, this shift wasn't just about weight loss, it reflected a deeper rebranding of obesity treatment, a change in how weight is medicalised, and the broader pressures of a society that increasingly seeks fast, pharmaceutical solutions to complex health and identity issues.

It’s also started broader conversations about how women, in particular, are affected by media criticism, shifting beauty standards, and the pressure to keep up with ever-evolving trends.

Some women who are not clinically classified as obese, or even overweight, have turned to these medications, often in pursuit of a thinner, more idealised version of themselves.

This reflects not just a personal choice, but a cultural moment where weight loss is increasingly seen as a form of self-optimisation, even in the absence of medical necessity.

But while access has expanded to more people, not everyone can afford these drugs.

In the US, the average list price for Ozempic is $936/month, compared to around £93 in the UK or €103 in Germany.

For patients without strong insurance coverage, or none at all, those costs are largely out of pocket, making the medication financially inaccessible for many who may need it most.

So what happens when a drug becomes wildly desirable but prohibitively expensive?

Low-income diabetics are often the first to lose access. They're deprioritised, priced out or caught in prescription backlogs.

Some are being forced to ration their doses and others are turning to black-market options.

The CNBC investigation, which you can read here, found cross-border black-market networks now trade in counterfeit or unapproved versions of Ozempic and Wegovy, moving products through online forums and private messaging apps without any quality control or medical oversight

What This Means for Marketers and Brand Strategists

The trend is already causing ripple effects into other industries.

Fashion runways are swinging back to ultra-skinny. Spring/Summer 2025 shows featured only 0.8% plus‑size looks, a drop from a brief inclusivity moment mere seasons ago. Critics in The Guardian, British Vogue, and Fashion Times flagged this as a direct fallout of the "Ozempic effect"

Some brands in the cosmetics industry are facing an identity crisis because when the ideal face becomes thinner through medication rather than contouring, how do makeup brands adapt when that’s what their campaigns always focused on?

Another observation has been the retailers adjusting their sizes. Has anyone else noticed this? It was actually reported not long ago that brands have been selling more smaller sizes and simplifying their size ranges, a sign that bodies on GLP‑1 drugs are shaping inventory choices behind the scenes

As these drugs suppress appetite and shift food preferences toward protein-rich, smaller portions, brands like Nestlé, Conagra, and General Mills are already adjusting, releasing ‘GLP‑1 friendly’ snacks, downsized packaging, and higher-protein product lines

Marketing's Role Under Scrutiny

What’s been interesting to hear are the conversations now happening behind closed doors.

Marketing professionals are examining their role in shaping beauty standards, with different companies taking different approaches.

Some brands are adapting pretty quickly, conducting focus groups to understand changing aesthetic preferences and updating creative briefs to reflect new beauty ideals.

Others are taking a more cautious approach, with some spending months debating representation strategies and potential consumer reactions.

And then there are the companies maintaining their stance continuing to focus on inclusivity messaging regardless of trending aesthetics.

The questions they’re asking themselves?

How do marketing campaigns influence consumer attitudes toward medical interventions?

What responsibility do brands have when beauty standards drive people toward expensive treatments?

How should messaging adapt when physical transformations can be achieved through prescription drugs?

What role do advertising strategies play in reinforcing unrealistic body standards?

Why are these questions important?

Brands need to be mindful that, based on both observation and data, we’re moving toward a more fragmented beauty culture rather than a single, dominant standard.

Social platforms like TikTok are now home to billions of views around movements like #BodyNeutrality, #bodypositivity signaling a broad appetite for diverse, non-traditional beauty standards.

And recent surveys show that around 50–53% of respondents support GLP‑1 drugs like Ozempic when used for medically indicated weight loss, but only 12% are comfortable with their use for purely aesthetic purposes.

Notably, younger consumers (under 35) are especially cautious, nearly half express concern that these drugs could further entrench unrealistic body standards.

At the same time, a lot of people are just exhausted!

There’s growing fatigue with the idea that our bodies must constantly be optimised, especially when the path to that ideal comes with a $1,300/month price tag, prescription hurdles, and medical risk.

Economic pressures are adding to that fatigue.

Inflation, rent increase, healthcare gaps, and food insecurity are making appearance-driven spending harder to justify for many consumers.

Large, high-cost beauty and wellness services are being postponed or dropped entirely.

But smaller indulgences, lipsticks, budget skincare, self-care rituals, are holding strong.

In fact, in the UK, beauty spending rose 11% in 2023 thanks in part to the so-called “lipstick effect,” where people opt for small luxuries during tough economic times.

Meanwhile, a Bain & Company report found that 2024 was one of the weakest years for the luxury goods market since the Great Recession, with sales flatlining at –1% to +1% growth and a loss of about 50 million aspirational consumers.

For some, using Ozempic as a cosmetic intervention may represent a new kind of luxury purchase, one increasingly out of reach for many.

And as history shows, recessions tend to reset our relationship with vanity. Eventually, survival outweighs aesthetics.

This all matters because it tells us where culture is going.

The brands best positioned for the future won’t be the ones chasing every new body trend or mimicking the latest trend. They’ll be the ones that stay anchored in values, brands that speak consistently to their audience’s identities, bodies, and lived realities regardless of what’s trending.

In other words, they stand on their own principles whatever that might look like.

I would maybe make a couple addition to this otherwise well-researched article: the jump from hourglass '50s to heroin chic '90s was a bit stark. Skinny, leggy models like Twiggy dominated the '60s-'70s and muscle was in during the '80s to early '90s, from Jane Fonda to Cindy Crawford. Which is why some would argue the next frontier becomes muscle again after everyone gets skinny with ease on Ozempic.